Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

BRICS expanding

The leading regional and international organizations that shape international order were all created at times of crisis. The United Nations Organization was formalized in April 1945, before WWII had come to a close and right after the Bretton Woods summit in July 1944, out of which came the International Monetary and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

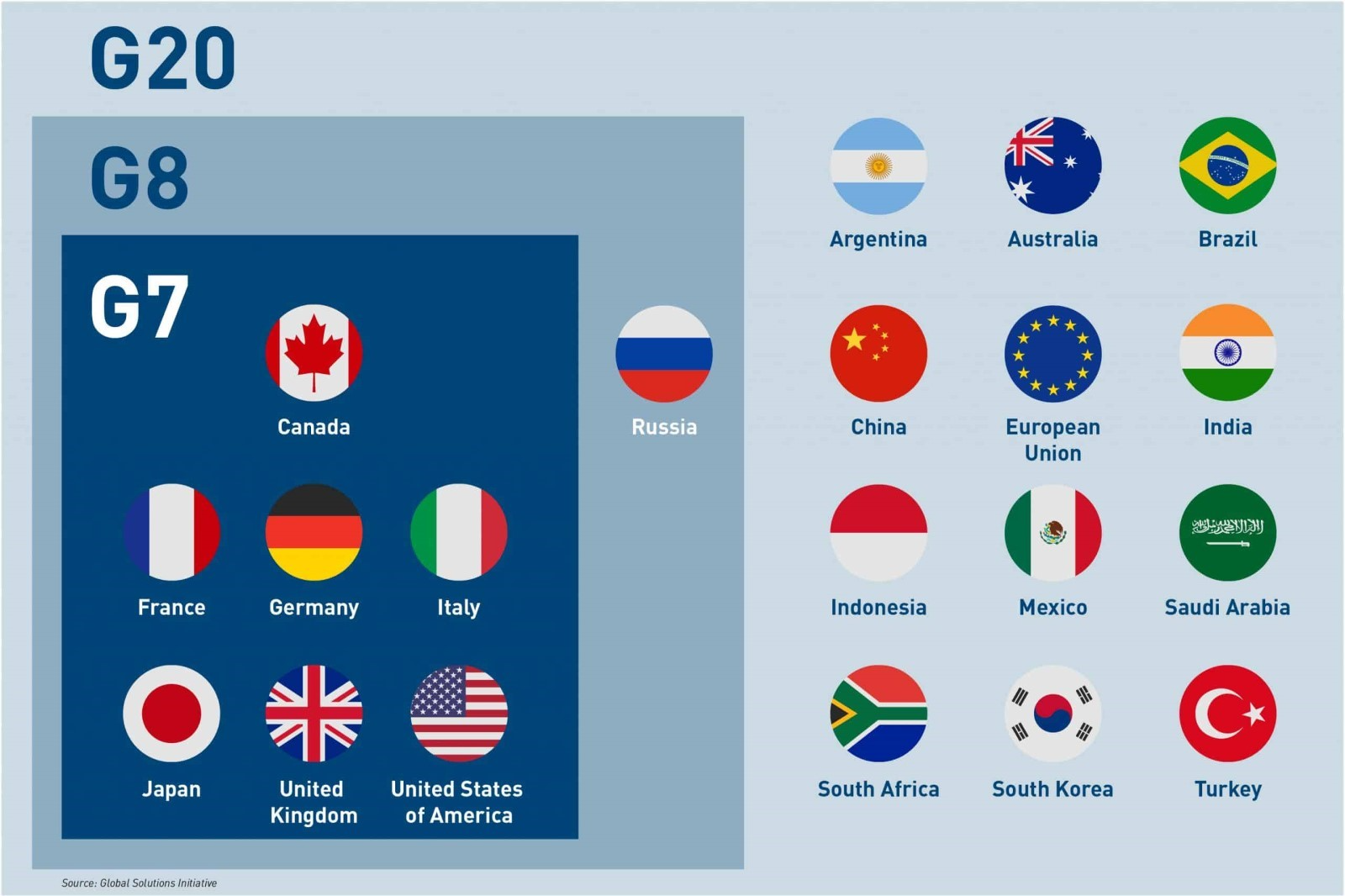

The Cold War necessitated the establishment of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) in 1948, NATO in 1949, and the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951. The G7 and its forerunner, the Library Group, came as a response from industrialized democracies to the economic crisis caused by the exponential increase of energy prices after the Yom Kippur war in October 1973.

The financial crisis of September 2008 motivated a transformation of the G20, which went from a subsidiary of G7/G8 on to become as central institution, alternative to its forebear organization, although it did not formally supersede it. In fact, there are three key differences between G7 and G20 which help explain some of the frustrated expectations toward management of large systemic crisis and lead to meaningful lessons on the more or less informal forums that emerge over time. First of all, G7 has always been a political, strategic, culturally homogeneous institution. That makes for stark contrast with G20, where there are no common values, and political and cultural diversity has always been the rule, within a framework of naturally diverging strategies. Secondly, G7 clung to a trans-Atlantic, or “Euro-Atlantic” community, or space - extended for a time to Russia, between 1997 and 2014 - while G20 attempts to hold in place some kind of regional hierarchy with a degree of strategic credibility, excepting perhaps the Middle East. Thirdly, G20 attempts to draw a formula for concert among political powers. Paradoxically, it has neutered that possibility. Seven or eight members would be the kind of number to make possible such an alignment of international powers.

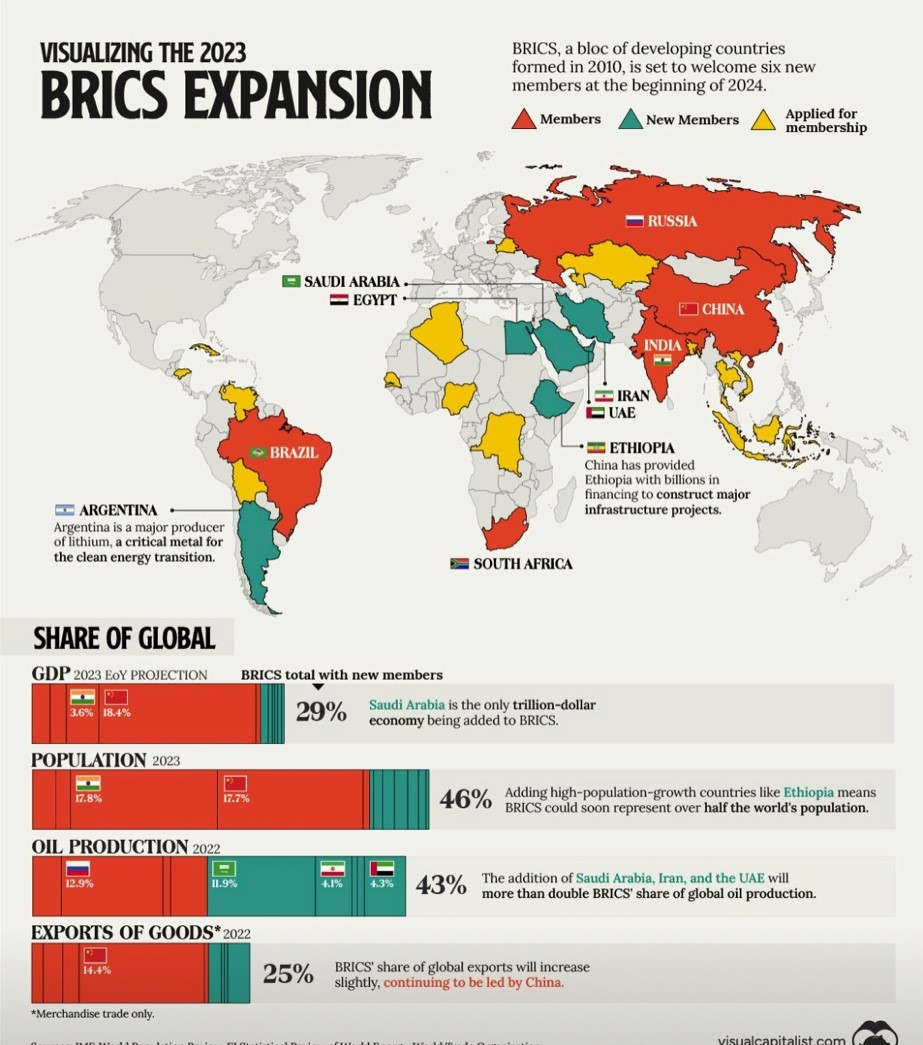

In this light, it seems safe to point out that it’s always been in the aftermath of seismic disruptions that systemic opportunities arise. So it was when a great financial depression hit its nerve center in the West, back in 2008-2009, and BRICS attained formal status one year later, with South Africa having joined Brazil, Russia, India, and China. So it seemed to be, again, when European security was called into question by the Russian invasion of Ukraine at a time when the western response finds itself out of sync across continents and BRICS adds six more members. In this light, we can now consider three important lessons on the first era of this particular group and, probably, a couple of outcomes from the second era that begins with the Johannesburg summit in August 2023.

The second lesson indicates that the scales of power tip heavily toward China. Measured by key power-projection indicators, the group has been China-plus-four, which is evidently expressed by the increase in China’s comparative economic quota, enough to swallow up the economic might of all the other members put together. Not to mention the erosion of Russia, whose GDP might at international level best be described as mid. The individual profiles of the six new member-states tell us that, for financial, political, and trade-related reasons, Beijing now has greater sway with the organization.

Finally, the third lesson is that the BRICS have scarcely used their joint power during their first stage. Congregating 40% of the world’s population and 25% of its GDP, what concrete, structural changes has the group brought to the international order, especially to the leading financial institutions that constantly come under fire, targeted by often just and legitimate criticism? In truth, hardly any changes. Except from time to time they’ve driven debates on how a few reforms are inevitable, along the lines the US already seems to follow. Even the establishment of new, Asia-centric financial institutions, has added to China’s arsenal in defence of its trade interests, growing countries’ external debt, rather than chip away at the dollar’s might, or provide an alternative to major Western financial institutions. Nobody is saying that, as evidenced by a few premature analyses that reduce everything to the quantifiable, that giving the BRICS+6 more aggregate global weight in terms of population (46%), GDP (29%), oil production (43%), or commodity exports (24%) will make the group more functionally coordinated, more systemically transformative or geopolitically coherent. Now we come to the two effects I wanted to bring up.

The first arises out of the geographic arc at the Johannesburg summit — up to 70 leaders attending and more or less formalized requests for accession (two dozen, give or take). This means many people regard BRICS as part of a strategy for integration of mid-sized countries into relevant decision centres, where balance with the western leanings of the past decades is more visible on economy, energy, defence, industry, and access to raw material of key importance in technological competition. It also means many have no qualms about Chinese leadership, its looming power, the dependency caused by ongoing concentration of bilateral debt or the kind of power that governs from Beijing. In other words, the western model is no longer attractive. We need to reflect on the way our democracies have been heading these past few years.

The second effect arises out of a trend shaping the emerging international order. We’re witnessing an attempt against fragmentation. But, unlike the bipolar arrangement that defined the Cold War and the unipolar moment that followed, I don't believe we’ll enter a period of orderly multi-polarity. What’s dawning is an order of archipelagos, multifaceted alignments, more fluid and transactional, dubious, opportunistic and even antagonistic behaviours where many mid-sized countries will avail themselves of any options at their disposal. Sometimes they will play with the West, others with BRICS. Whoever affords them the best power-projection methods. This is why BRICS expansion will not prove uniform, harmonious, or cohesive.

Obviously metrics of economic power, energy or population are fundamental to evolving power balances, but above all they illustrate potential in aggregate, not a stable, cohesive reality. As I endeavoured to demonstrate, there are major divides caused by so many diverging interests, especially along the Beijing-New Delhi axis, once again expressed by Xi Jinping’s absence at the latest G20 summit in New Delhi. There’s a hard road ahead until the kind of integration we see in the West emerges. As history and specialty literature show, consolidating a security community that can project a clear model that will find a place in any international system demands, among other things, a shared political cultural, institutions and governing regimes on the same page, high mutual trust levels and, if possible, a common threat to bring everyone together. In broad strokes, that was the basis for creating, consolidating and growing western institutions in the post-war period: Both financial ones (IMF, World Bank) or political, economic and military ones (European Union and NATO). Until we see evidence to the contrary, it does not look as if the BRICS group possesses that level of interconnection, alignment and political culture, no matter how many member-states it brings into the fold, even if they could be brought together by some kind of anti-western sentiment.

That doesn't mean the group doesn't deserve close scrutiny. Starting with the relationship between India and China, which is structurally tense, fraught with mistrust, from building tension around land borders to the language the two nations employ, from their military investment to technological competition. Both countries will feed spaces for aggravation that Europeans and North Americans may be able to exploit. The same goes for China and Russia. The matter of if and how they clash would form the basis for a different essay. What seems to converge upon the legitimate rationale for expanding BRICS, or creating new, non-western institutions, is a justified critique of the lack of reform within institutions that have underpinned globalization these past few decades, depriving the system of more significant representation of current economic, population and political equilibriums.

It would therefore prove worthwhile to reconsider the logic of representation and power in the decision-making bodies of financial organizations that have set the course for the present international order, so as to reflect the newer distribution of power, avoiding ballooning resentment that would then lead to a proliferation of rival bodies, setting in stone this perception of a series of airtight international blocs. The same goes for reforming the Security Council. By now it should have brought India, Japan, and Brazil into the fold. The council’s hands are tied when it comes to handling major security crises, and one of its seated members, holding veto power, is in gross violation of the United Nations Charter. Postponing reform is a step toward lasting irrelevance.

We can however state that it is always more difficult to go around the inflexibility of formal organizations than to broaden or alter procedures through more elastic forums that have no permanent governing bodies or deeply rooted bureaucracies, such as BRICS, the Shanghai Organization, G20 or even G7. That is true. But that’s what gives Beijing a bit of an edge. They repeat this mantra of non-representative western hegemony to most countries in the world, the ones locked in this “developing countries” descriptor, that “global South” which, as a bloc, sustains each new strategic initiative from China. That is why China has sent more troops on UN missions than the other four permanent members of the Security Council put together. China has become the second largest source of funding for the UN and its field agencies.

We can take a fatalistic view of the world’s current heading as inevitable, or we can use our brains to enhance coordination and integration to take advantage of existing misalignments. Time is not however on our side. If Trump gets elected next year, he won’t play that game.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.