Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

Trumpism: Roots in American History

The movement that propelled Trump to the White House and survived his electoral defeat in 2020 finds numerous echoes in US History. Although the 45th president has never formulated any political philosophy or fomented any specific current, an analysis of his term reveals a few political aspects rooted in America’s political history.

Let’s focus on four fundamentals: first, populist ideas meant to galvanize an aggressive dichotomy between the people and the elites; second, animus against the separation of powers and constitutional republican values; third, nationalist and tendentially isolationist ideas; fourth, authoritarian practices that reject the opposition’s legitimacy and the peaceful transition of power. One can argue that Trumpism does not exist as an ideology or doctrine, but it is more than an aggregate of stances and ideas latent in American history which resurface from time to time. The fact that they are promoted by a figure as atypical as Trump, at a moment when the press and social networks have attained such power, has given substance to a widespread movement growing beyond the candidate figurehead.

Trumpism also resembles political trends observable across most of the world. Based on the concept of authoritarianism, defined in the 1970s by political scientist Juan Linz to describe governments that were neither democratic nor totalitarian, Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way added “competitive authoritarianism,” a term which they used to describe post-soviet regimes equipped with institutions that were outwardly democratic. Others prefer the word illiberalism, a concept mentioned by Pierre Rosanvallon with regard to Caesarism, made popular by Fareed Zakaria, who couched it in terms that liken it to populism: illiberal lawmakers backed by universal suffrage who, once in power, use the powers of government to deprive citizens of their fundamental rights, neuter checks and balances and undermine the rule of law, controlling the courts and the media. So they build a bastardized democracy in which the rule of law is presented as an obstacle to popular rule and democracy itself.

If we turn back the clock we’ll see that the roots of Trumpism aren't alien to the US. The Know Nothings of the mid-19th century ran on a nativist, anti-immigrant and white nationalist platform. Toward the end of the century the Populist Party was home to farmers who'd been displaced or had their livelihoods jeopardized by industrialization, and they took some of their cues from anti-Semite and anti-immigrant discourse. William McKinley’s successful run for presidential office in 1896 was designed as an answer from the industrial block to William Jennings Bryan's populism, who championed high tariffs on imported goods, tolerance of racism and anti-Black violence, and a foreign policy approach that put America first.

At the end of WWI, the conservative forces of rural America gazed with suspicion upon the new face of a country where women had found emancipation and entered the workplace, African-Americans had gained the right to vote (while that right was enshrined in 1870, they did not necessarily get to use it), and immigrants (non-white Europeans) had never made up such a large percentage of total population. At the same time, farmers all over the country sank in debt. Responding to these developments, deemed threatening to the American way of life, a populist, conservative reaction grew around the notion of “America first.” This response congealed in the rise of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), accreting eugenics, nativism, and laws that drastically curtailed right of entry to immigrants based on their country of origin — “America must remain American,” said Republican president Calvin Coolidge in 1924. Donald Trump’s father took part in a 1927 KKK rally in New York.

Charles Lindbergh addresses the America First Committee in 1941. Source: AP

Charles Lindbergh addresses the America First Committee in 1941. Source: AP

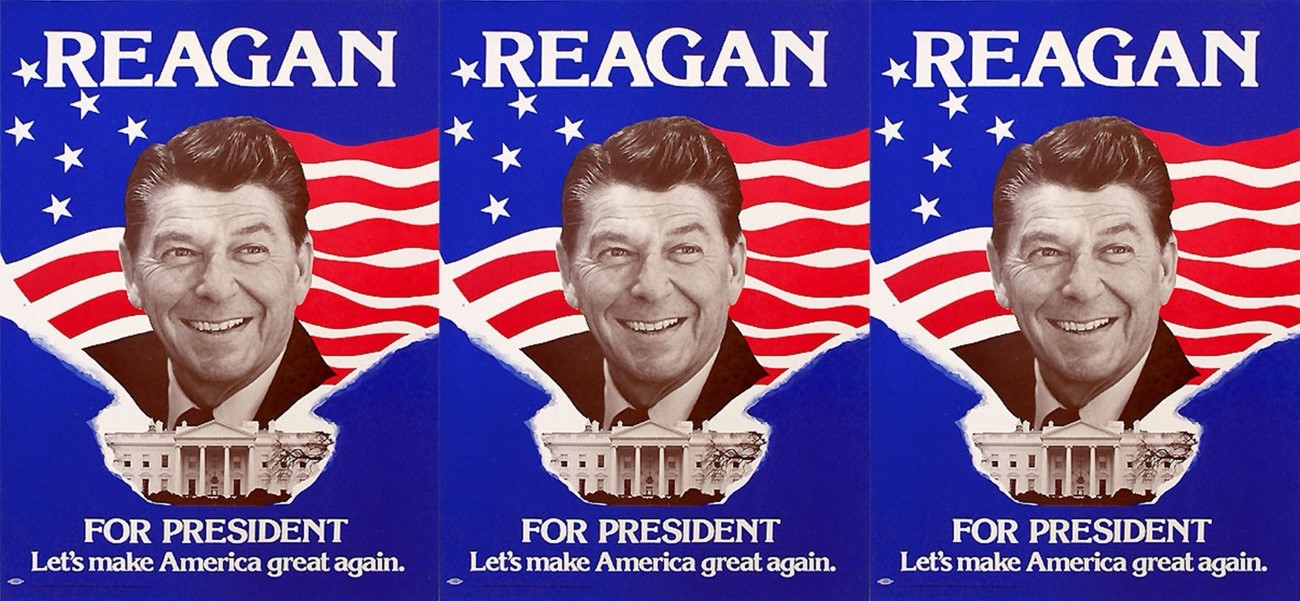

Although this movement ebbed a little with the New Deal, it didn’t go away altogether. Following in the footsteps of its late 19th-century anti-imperialist predecessors, the America First Committee tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to keep the United States from participating in World War II. It was disbanded in December 1941. Non-interventionist conservative voices lost more ground as the US took on a new international role in the “free world” as Great Britain withdrew, while domestically, Dwight Eisenhower’s moderate, liberal republicanism worked in the background to end the frenzied, illiberal persecution of communists by Republican senator Joseph McCarthy. Never homogeneous, the conservative constellation began to evolve in the 1950s. As a new right-wing intellectual movement gradually coalesced, the old, populist and conservative right, which historian and philosopher Paul Gottfried calls “paleo-conservatism,” didn't disappear entirely. You can see its fingerprint on Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign, which deepened the ties between the South and the more conservative factions of the Republican Party, and on the reactions led by two Californians: Richard Nixon against the “cultural elites” and Ronald Reagan against “big government.”

In the 1990s, contrasting with triumphant international liberalism, which prevailed at the end of the Cold War and sought to convert Eastern European economies, paleoconservative voices, rare and often given to extremism until then, gained more prominence. Pat Buchanan, advisor to presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan, became the champion of this movement. In 1992, Buchanan ran in the Republican primaries, bringing back the “America First” slogan, which Trump would reuse later on (let’s take a moment to remember KKK leader David Duke ran in the same primaries). His platform demanded lower taxes, less immigration, a harder stance on the culture wars that had polarized the country since the 1960s, more attention paid to domestic policy and a return to protectionism as well as a form of isolationism. Such discourse would be picked up by Trump almost a quarter-century later.

Source: United States Studies Centre

Source: United States Studies Centre

When Republicans secured a Congress majority in January 1995, America’s polarization was embodied under the leadership of the Speaker of the House of Representatives and his response to Bill Clinton’s policies, not to mention to the very personality of the Democrat President. However, economic prosperity at the time kept people from embracing nativist, protectionist rhetoric. Years later, the shock of 9/11 stunned the US and united the country in sorrow and anger, at least for a while. But the fiasco of the Iraq war reopened the scars of Vietnam and roused once more the time-tested, anti-war sentiment espoused by libertarian sectors who reckoned wars were fought at Americans’ expense.

The great recession of 2007-2009 catalysed all sorts of resentment and frustration — among the middle class, whose standard of living took a hit, but also among the working class, especially African-Americans and Latinos, who found themselves living in the streets thanks to the subprime crisis and a banking system whose credibility had tanked. Unsurprisingly, conservatives placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of federal government. Barack Obama’s election would be the straw that broke the camel’s back for nationalist, populist conservatives. The economic reforms proposed by the Bush administration in 2008, per Obama, were rejected by an increasingly virulent group in the House of Representatives, and the Tea Party, a heterogeneous, libertarian, conservative and subversive group, would be created in January 2008 as a response to Obama’s rise to office. Whether they belonged to this mostly forgotten group or not, the majority of Republicans stood in the way of every reform Obama sought to implement, an obduracy understood as an attack on the very working of democracy and a contribution to the polarization of American politics.

Sowing the fertile soil of disenchantment, fear of social mobility, resentment, nativism, racism, extreme nationalism, protectionism, and the rise of the evangelical right, Trump instinctually revived several paleoconservative and populist ideas achieving a surprising victory in 2016, continuing to electrify crowds before the 2022 midterms and the presidential election of 2024. It’s easy to draw a line from political figures such as Huey Long, Barry Goldwater, and George Wallace through Newt Gingrich and Sarah Palin on to Trump. They all told similar stories and tilled the same field. However, Trump has powerful backing, either tacit or explicit from big tech leaders, whose companies circulate disinformation, hatred, and conspiracy theories, wholly reshaping public discourse; and the accelerating transformation of the international order, with state-capitalist, authoritarian regimes praised by Trump, realigning the style and enforcement of political power, also propels him forward. Never in America’s history have these three currents been so in sync — nativism, authoritarianism, disinformation — which only brings more disruption, more danger, and dystopianism.

Text written before November 1, 2024.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.