Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

The Three Seas and the Meaning of the Middle Corridor

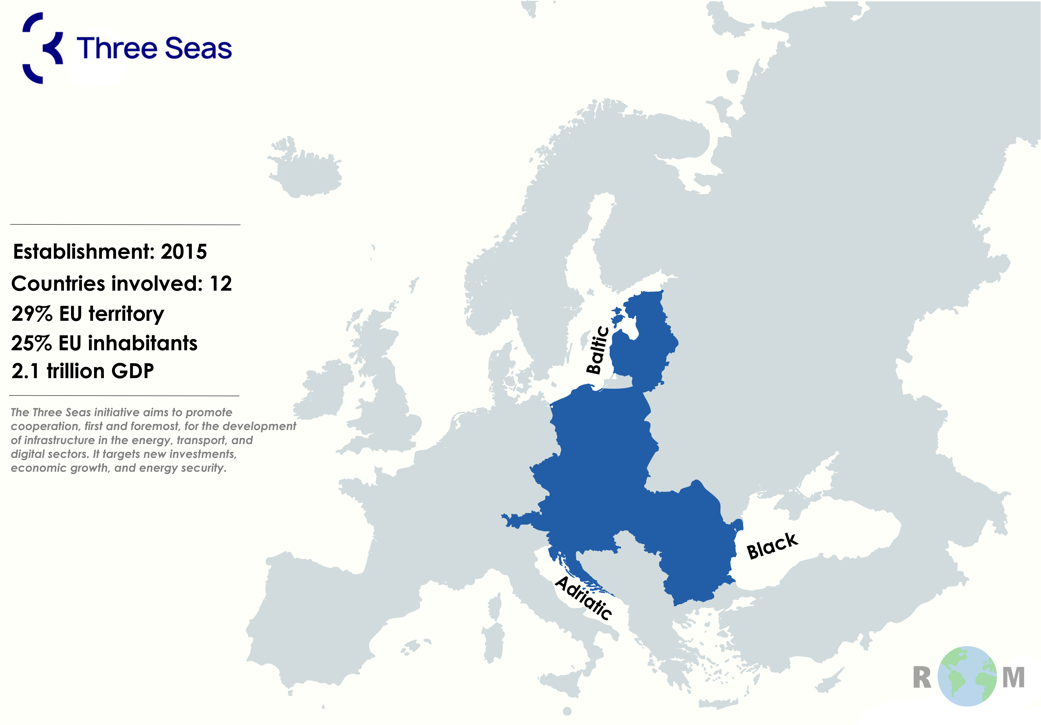

Launched in Dubrovnik back in 2015, with 12 EU countries covering 30% of its geographic reach, the Three Seas Initiative (Baltic, Black, and Adriatic) lays out a network for energy supply, communications and infrastructure which objectively intends to deny Russia its hold over several countries insofar as it relies on energy, and check Germany’s political influence on Community decision-making.

Berlin did not greatly appreciate this forum, given that the 1340 km of the Backbone pipeline connecting Lwówek in Poland to Sisak in Croatia, plus the Swinoujscie gas line running from Poland’s Baltic shore to the Krk islands of Croatia on the Adriatic are two pillars of an energy supply chain from north to south competing directly with Nord Stream 2, which had been designed before the war in Ukraine to connect Germany and Russia bypassing Poland. While the project gives Croatia a new status beyond the Western Balkans — a phrase many local politicians would rather not employ — it also serves Poland insofar as it presents the country as a preferential connection for liquefied natural gas exports, solidifies its independence from Russia and makes it more of a counterweight to the German colossus.

The Three Seas Initiative (3SI) has not only gained momentum from the Russian invasion of Ukraine but also broadened its scope, advancing a history of successful projects. Understanding regional nuance and continent-wide challenges, such as energy security and war, the initiative has become a platform that addresses pressing needs. The grouping arises from a shared history of geopolitical change and economic transformation as participating states recognize the importance of connectivity and cooperation to uphold their collective interest. It’s an auspicious new beginning for Central and Eastern Europe, which haven’t always been too cooperative, scarred by a long history of political and territorial dispute. By gathering resources and knowledge, they seek to bridge the infrastructure gaps of old, stimulate economic growth and reduce dependency on outside actors. Recent 3SI projects demonstrate a commitment to bolstering connectivity and resilience in the regions. Take as examples infrastructure such as Via Carpathia and Rail Baltica, meant to improve transportation networks, facilitating movement of people and goods across the entire region. Furthermore, projects in the energy space, like the Baltic Pipe and the synchronization of power grids, will further strengthen energy security, making states less vulnerable to outside disruption and reinforcing their self-sufficiency.

A Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund has been created, a pillar of the concrete impacts the initiative has had on regional development. In a mere four years, the fund has invested over 700 million Euros in renewable energy projects, transportation, logistics, and digital infrastructure. The fund also seems adequately positioned for collaboration with key regional institutions, such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), an indispensable partner in several sectors. For example, the fund's investment on Bulgaria’s seaport at Burgas appears poised to create an alternative hub on the Black Sea — a body of water now central to current international tensions — offering a competitive inlet into the European market to international traders. With scalable infrastructure already in place, it is likely to become a relevant logistics hub that will make it much easier to rebuild Ukraine over the coming years.

Yet another example is Cargounit’s purchase of locomotives in Poland. The 3SI investment fund holds a 100% stake in Cargounit and this is the biggest acquisition of its kind in Poland’s history. It also serves as a statement of intent regarding the improvement of railway connections and advancing greater reach for supply chains among partner countries. Furthermore, investment on seaport and railway infrastructure looks to increasing the EU’s industrial export capabilities, benefiting its economy and breathing new life into international markets and trade. Realizing that theory has become reality is no doubt a turning point. It opens new doors to a region historically known for its untapped potential. Despite all the hardships of the past extended into present-day war, the region shares pathways for sustained development, meeting urgent needs.

In addition to improving transportation, renewable energy projects seek to improve energy resilience where countries have by and large sourced their supply from Russian outlets. Take the Fund’s investment on the Polish group, R.Power Renewables, for example. It is indicative not only of the progressive embrace of renewable energies but likewise of the block’s willingness to work with other European partners, including Portugal, where it has already established a presence. Another example would be the Fund’s entry into Enery from Austria, a renewables platform focusing on solar, which has expanded its footprint to encompass over ten countries in the region.

The biggest accomplishment to date is that new light is shed on the paramount need for investment in infrastructure along the north-south axis and the geopolitical possibility of advancing integration with Euro-Asian markets. The brand’s growing value has been demonstrated at the latest summit, including Greece as a member state, bringing the project’s reach into southern Europe. Ukraine and Moldova have themselves been confirmed as partner nations, evincing 3Si’s potential as an instrument that amplifies European integration and stability. And what's more, 3SI now draws attention from the four corners of the world. At the latest summit, several Asian delegations attended, including an enlarged Japanese contingent. Note also that the South Korean embassy in Romania has played an active role promoting investment in Central Europe. Seoul has developed a cooperative defence partnership with Poland and notably guaranteed a direct flight route to Lisbon in Portugal. This exemplifies how the powers of the Indo-Pacific region, including South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and India, see the benefits of European stability and the continent’s prosperity as an economic opportunity to intensify a strategic relationship to counterbalance China’s preponderance.

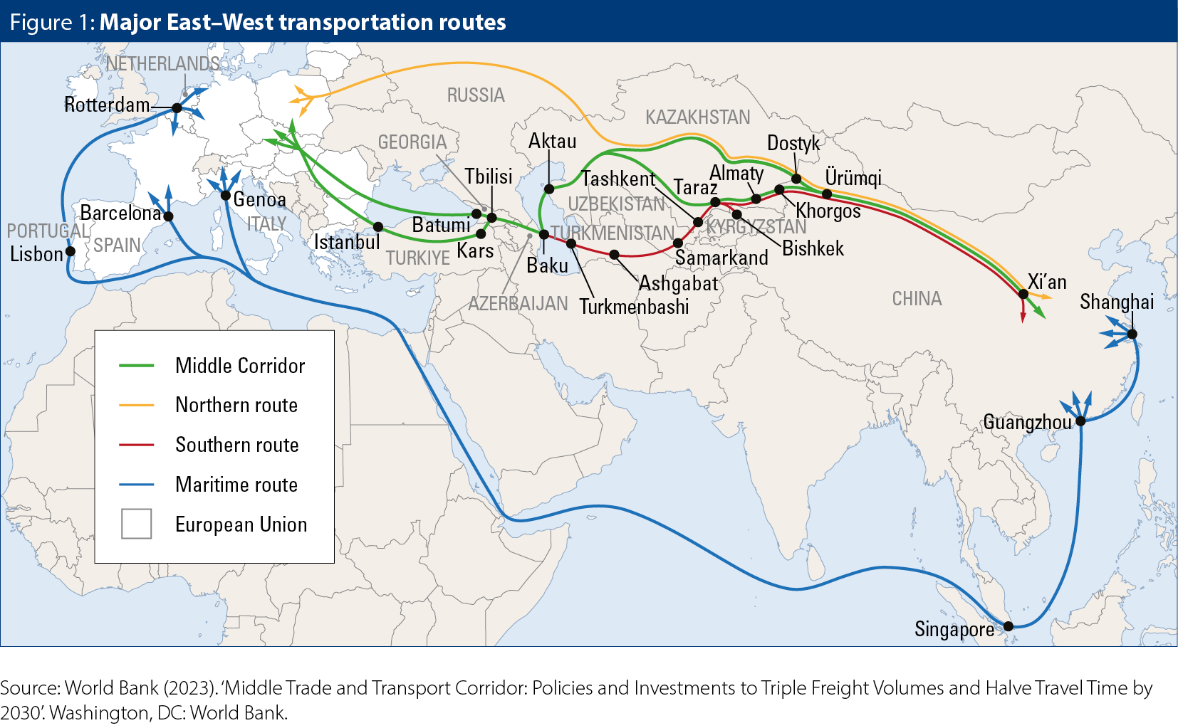

Finally, we have increasing acceptance that strong north to south infrastructure in Europe could be a powerful factor for Euro-Asian integration, reinforcing connections with Finland, as well as Europe’s presence in, and access to, the Arctic. Through the Black Sea, it connects to the Middle Corridor via the Caucasus, and this is where Georgia plays a pivotal role. It reaches into the key markets of Central Asia, mainly China, a connection that could more broadly incorporate the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Indo-Pacific, Africa and, through the Atlantic, the entire West. At a time that exposes the pain points and the value of security in diversified logistics supply chains and energy supply, interlinking these routes and structures has attracted the interest of governments and corporations alike.

Before the war in Ukraine, China seemed ambivalent on the promises of the Middle Corridor. Getting to Europe via the traditional northern route, through Russia, was three times faster. While that route was measurably longer, it offered better railway infrastructure, fewer customs checks, and it avoided the Caspian. So Beijing saw the Middle Corridor as a complementary channel at best. Meanwhile, Turkey, the southern Caucasus and Central Asian countries that would benefit from infrastructural improvements and possibly

the movement of goods and commodities did not have the resources to invest on a scale that would revitalize the route. However, in 2022, container shipping grew by 33% compared to the preceding year. This owes to the fact that China has rerouted most of its EU-bound exports away from the northern route in light of western sanctions on Russia to focus on the sea lanes from the Strait of Malacca to the Suez Canal and the Middle Corridor.

In October, Georgia hosted the Tbilisi Silk Road Forum, postponed due to the pandemic. The goal was to leverage the country’s strategic position and the framework of free trade agreements with EU and China. One of the announcements coming out of the forum was the creation of a joint enterprise, the Multimodal Central Corridor with Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, intended to facilitate inter-government cooperation among the railway systems of the three countries so as to provide scale for a shared logistics operator which has been created in the meantime. Back in 2021, trade from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan constituted about two thirds of the Middle Corridor’s throughput and this quantity doubled in 2022. For example, Kazakhstan and Georgia saw a 45% increase in business volume, while Azerbaijan’s grew by 72% compared to 2019-2021. As a consequence, many forecast that trade between China and the EU will grow approximately 30% by 2030.

We can extract two conclusions from all this. First, that integrated investment on infrastructure, connection, trade security, and autonomy in logistics across the European continent makes its economies more dynamic and rebalancing inequalities more of a material possibility. That's fundamental to check pushback against democracy and whittle away at populist pressure. Secondly, economic integration, well-regulated, featuring reciprocity with Asian markets, serves as a means to subtract from Russia’s trade and economic influence and bring China closer to European interests. All of the above, in light of present geopolitics, is of capital importance.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.