Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

Notes on the expansion of the European Union

Geopolitical motivations have always driven the expansion of the European Union, which is as true of member-states as it is of those seeking accession.

Geopolitical motivations have always driven the expansion of the European Union, which is as true of member-states as it is of those seeking accession. Let us recall two groundbreaking cycles over the past forty years: integrating Central and Eastern European countries was a way to forestall any vacuums regarding Russia’s intentions, bolstering independence and inclusion in the common market; and before that, bringing Greece, Spain and Portugal into the fold protected their unfolding democratization processes, guarding against worsening economic and political instability.

The context behind such accessions is not however comparable to what we’re here to discuss today. The nature of the EU and its geopolitical stance have both changed. Over the past two decades, the EU has sought to develop common foreign policy and security instruments, anticipating an environment of greater vulnerability, and it has endeavoured to preserve a situation where fundamental rights, democracy and the rule of law continue to be attractive propositions. Which apparently they still are. Or there would be no new expansion process.

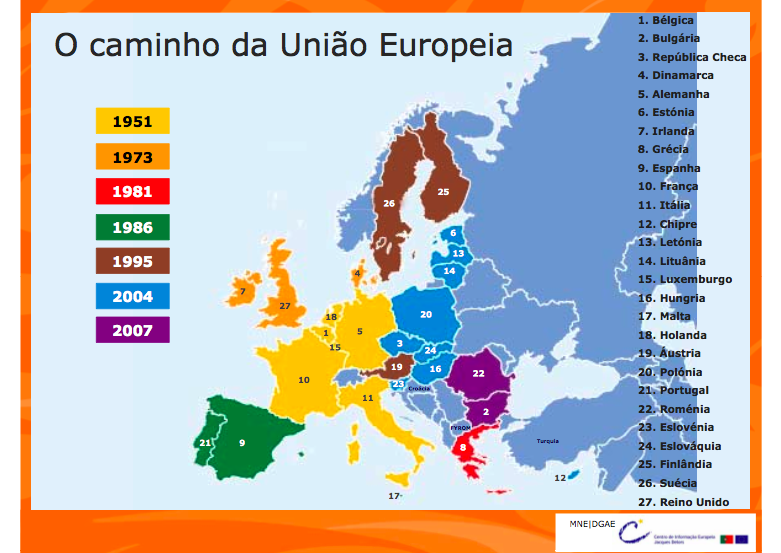

[The EU’s path: Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, The Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, United Kingdom]

However, the EU must not approach geopolitical expansion through an exclusive lens of vulnerability. The impetus behind accession for Ukraine or Moldova establishes the EU’s appeal as a provider of security and a bastion of democratic values. Both constitute compelling arguments for trust in the future; maintaining value-driven geopolitics is one of the advantages the EU can draw on. However, for the past two decades, expansion policies have been unable to anchor democracy and the rule of law across the western Balkans in any substantive manner. Instead, backsliding into autocracy has become more competitive. One of the aspects which might explain that lies with the priority that EU attributes to security over democracy in the region, fearing potential flare-ups of inter-ethnic violence and aggressive historical revisionism. Facts do not contradict this concern, but they also mean that advances in negotiation with Ukraine and Moldova for the past year have moved at a much brisker pace than those framed by the parameters established for the western Balkans for the past decade.

Accommodating these in the common market with the backing of the European Commission will let the EU reorient some internal economic and social cohesion and, for example, mitigate the region’s brain drain. Gradual integration into existing community programmes will also let applicants help define the rules they shall abide by, emphasizing the benefits cooperation brings citizens, putting pressure on their governments to uphold community norms and thus promote integration.

Expansion has proven one of the European Union’s most successful strategies. It is, second only to the peace secured among the leading continental powers, Europe’s main political feat over its long history. Integrating new countries which, through sovereign choice, decide to align their constitutional frameworks, political values, economic fabric, and democratic principles with a shared whole of subsidiary rules has, by and large, worked to the benefit of all. This sort of benevolent empire of the rule of law has been one of the Union’s most interesting contributions toward the history of international relations, a process keenly analysed by Jan Zielonka in his title, Europe as Empire.

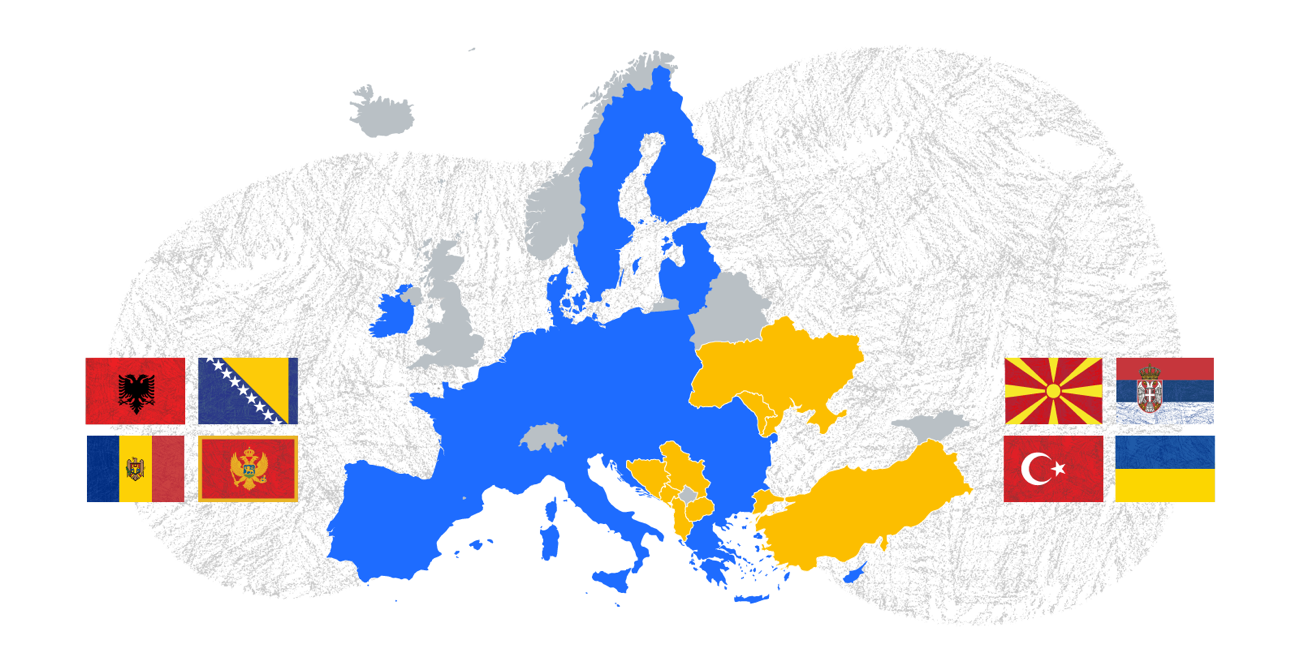

Today, on the verge of a new expansion to perhaps nine more nation-states with similar internal dilemmas to solve, but also distinct national contexts (six of the western Balkan nations, plus Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia) — I’m consciously setting Turkey aside for now because it seems to pose rather more specific conditions to me — it is worth our while to ask a few questions about what is to become of the greatest political transformations in post-war Europe, which has formed itself around the institutional logic of intercommunicating circles between a political European community (that converges on geopolitics and bilateral agreements with the EU), association agreements (that follow community rules, centred on the single market but preclude the need to deepen formal ties), full-fledged members of the EU outside the Eurozone which however do rigorously abide by its Treaties, and full members of the EU within the Eurozone, themselves fully committed to its Treaties. Portugal should remain a part of the inner circle of integration.

Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu

Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu

The EU growing to 36 member-states (EU36) would boost its internal market of 447 million to a staggering 513 million people, bring in new investment opportunities and take down obstacles to labour movement, which would allow for the recruitment of workers indispensable to our demographic situation and several sectors of our economy.

Secondly, the new expansion would add aggregate value to the EU as it competes globally over raw material critical to energy and technological transition, completing a common arc of shared geographic security, integrating new markets with strategic infrastructure and access to new and important trade routes.

Thirdly, Ukraine would become the largest target for the EU Common Agricultural Policy, outweighing France due to the sheer size of its agricultural sector, with 25% of the EU’s productive areas, providing the EU with bigger leverage in its back-and-forth with North Africa and the middle East. On the matter of EU Cohesion Funds, expansion to countries with even lower per capita GNI will have countries like Portugal sharing a smaller piece of the budget pie, unless it isn’t substantially reinforced by increasing contributions from member-states or pulling in new revenue. All of this points to the urgency of using PRR, PT2020 and PT2030 optimally so that over time we can mitigate the impacts of a smaller proportion of structural funds coming in.

In fourth place, contrariwise to the historical trend of expansion, the next six member-states may join the EU before they join NATO, which will value article 42.7 of the Lisbon Treaty, the mutual defence clause, while remaining outside the purview of the Washington Treaty’s article 5. Now this could be seized upon by Russia to undertake new sorties, take advantage of divisions and pain points in the EU joint strategy framework, which makes our strategic autonomy a priority, along with investment on defence, and coordinating security doctrines, for example, between the increasingly powerful Polish military and probably the Ukrainian military, in addition to effective nuclear deterrence from the United Kingdom, which entails closer strategic ties with London. Furthermore, it is prudent to consider that Donald Trump returning to the White House will potently reinvigorate Republican positions on the USA’s withdrawal from NATO and other organizations, which makes European autonomy even more of a priority, the vulnerability of our security more evident, and the world a more dangerous place.

These and other trends will shape the coming years of European policy and deeply impact our lives. Companies, politicians and society at large must anticipate and discuss challenges of such magnitude, preparing the country for the risks and opportunities of the process. Whoever looks at the coming expansion through the lens of the past can't perceive the big picture with all the new colours it contains. Nor can they protect their interests.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.