Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

Houthis and World Trade

The past few months have, on a daily basis, shed light on the ever closer relationship between geopolitical shock, interethnic conflict and forced changes to international economies and trade.

The past few months have, on a daily basis, shed light on the ever closer relationship between geopolitical shock, interethnic conflict and forced changes to international economies and trade. States, companies and private citizens live in a spiral of non-stop events, almost all of them interconnected, arising from complex causes and dystopian effects that are hard to monitor or even anticipate. All of them disruptive enough to demand new prep work in political and economic decision-making.

Such is the case with the layers of drama, players and conflagrations raging endlessly across the Middle East, influencing the options of major oil and gas producers, the dynamics of international organizations, the emotional climate on western university campuses, the choreography and efficacy of diplomatic efforts, the sustainability of geopolitical alignments, or the way groups mostly written off by the outside world suddenly stepping up to the world stage. Which brings us to the Houthis in Yemen and the impact of their strikes on major merchant vessels between the Indian and Atlantic Oceans via the Red Sea, connecting the great Asian ports of Singapore and China to key European ports in Rotterdam or Hamburg, a lane that carries 40% of trade between Europe and Asia.

So we should take a closer look at the wider region of the Indian Ocean, a sea that laps upon over thirty countries representing a third of world population. These countries demonstrate the importance of the ocean and its coastlines — 90% of world trade relies on the shipping lanes of the Indian Ocean. It is on the littoral that demographic growth, climate change, rising sea levels, scarcity of potable water and political extremism acquire a vividly geographic visage. From the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal we can trace an arc from Somalia to Indonesia, a region ailing with timid institution, crumbling infrastructure, and youthful population seduced by extremism. This geography ranges from the Red Sea through the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal and the waters of Java and South China.

On the Indian you may also find the main routes for oil transportation, as well as the principal choke points for world trade: the straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, Ormuz and Malacca. Forty percent of hydrocarbons sail through the strait of Ormuz and 50% of the capacity for all merchant fleets in the world traverses the strait of Malacca, making the Indian Ocean the busiest transnational contact point on the planet. So we have set the stage for the recent worsening of trade security from the Red to the Arabian seas, linked by the Gulf of Aden, as an expression of prolonged civil war in Yemen and, above all, of the military capabilities the Houthis have demonstrated, which merits analysis.

The Houthis began to mobilize in the late 1980s as a revivalist movement seeking to end religious, political, economic and cultural marginalization starting with the creation of the Arab Republic of Yemen, led by Ali Abdullah Saleh between 1978 and 2017, the year the Shi’ite group assassinated him at the capital, Sanaa. The seeds of sectarian tension between the Sunnite majority, backed by Saudi Arabia, and the Iranian-backed, Shi’ite Houthis were sowed over three decades. Unsurprisingly, the Yemenite government has gone through a number of civil war cycles between 2004 and 2010, tension ramping up with the American invasion of Iraq. A more volatile, deadly dynamic came into play in 2014, when Syria plunged into civil war and Israel, Hamas and Hezbollah lived through intermittent acts of belligerence.

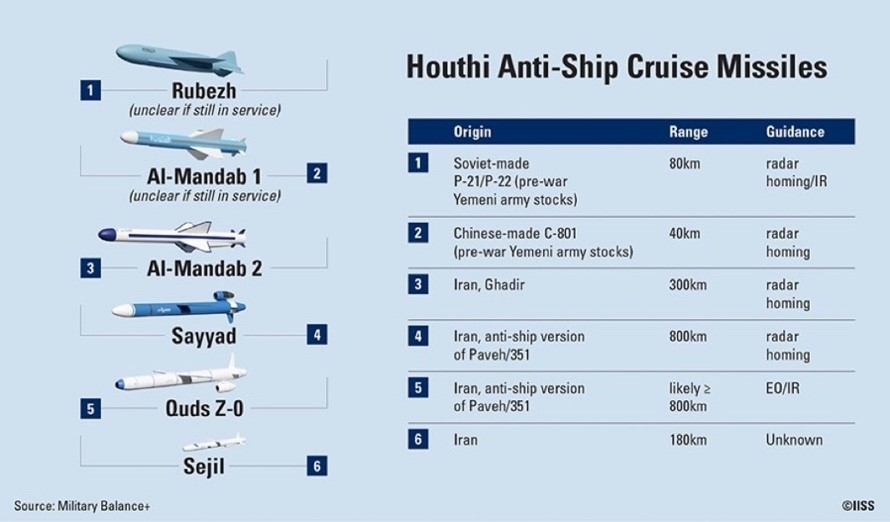

Let us take a time leap into 2023. Israel has mounted a military response in Gaza following the Hamas attack in October 2023. The Houthis’ military spokesman inaugurated recent hostilities as he published pictures of an Israelite vessel set ablaze. Pictures taken by cameras held by Houthi captors and disseminated for the world to see. Heavily armed gunmen had jumped out of a helicopter onto the deck of the Galaxy Leader, a freighter belonging to an Israeli citizen, capturing the vessel and about twenty crewmen. In early December, another statement scaled up the threat to “ships of any nationality sailing to the Zionist entity,” although one may conclude that the following strikes demonstrate that vessels do not need a clear link to Israel to become targets. Until now, over 200 drones and short- and long-range missiles have been deployed against international vessels sailing under more than fifty national flags, which turns the Houthis into a disruptive factor bleeding out of Yemenite borders, surprising for their military capacity and willingness to vie with American, Israeli and other allies’ protection. The globalization of the Shi’ite arc which began in the Middle East is now in full swing.

The Red Sea is one of the main arteries of world trade. Some 12% of the world’s oil and 8% of its natural gas trade crosses the Red Sea. European markets, having diversified their sources given the Russian invasion of Ukraine, increased their oil acquisition via this lane by 60%, which only underscores its importance. Access to the Red Sea requires passage through Bab al Mandeb, a 20-mile wide strait with Djibouti to the West and Yemen to the East. Several major shipping companies — seven of the 10 largest transportation companies, including Maersk and BP — have decided to discontinue shipping through this corridor and many others have turned to the more southerly route on the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope and then up along West African shores. 25% of sea traffic has been re-routed over the past month. This alternative lane piles on another ten to twelve days of sailing between Asian and European ports, which increases costs rather substantially (two to five times the freight rate) and delivery schedules, yet also entails exposure to new piracy hot spots on the Gulf of Guinea. Faced with such levels of maritime risk and insecurity, with far-reaching economic impact, the US and the EU have announced the formation of a multinational naval coalition to patrol the southern Red Sea and neutralize several command-and-control nodes of Houthi military power on Yemeni territory, using means from Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East. The United Kingdom, Bahrein, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Australia, South Korea and Japan have joined this effort. Note that the coalition does not include China. China has a naval base in Djibouti and considers the Red Sea a key component of its Belt and Road initiative.

Impact on world trade is significant: insurance premiums are through the roof and several leading container shipping companies have had no choice but to modify their strategic plans and take on the risk entailed in switching to other lanes. Longer trips will affect the supply chain and may ultimately affect consumer prices. For example, the Portuguese textile sector, heavily reliant on Asian raw material, has already taken a hit from the threefold increase in maritime freight rates. As to the distribution sector, impact is more noticeable on two-week delivery delays for specialized retail (electronics, computers, and furniture). Large auto manufacturers running operations in Portugal anticipate higher production costs, and the renewable energy sector feels the pain of late deliveries on solar panels, which drives up costs and affects project schedules. Should this level of insecurity and disruption to logistics in the region continue, there could be impacts on the inflation cycle, which had dipped over the past few months, and the price of raw materials, potentially jeopardizing several recent national and European measures, and that would in turn slow down economic recovery, especially in the Euro zone.

After ten years of civil war in Yemen, which has claimed so many lives, yet so low on the priority list of the international community — despite the Houthis launching over a thousand missiles and drones at Saudi Arabia, and striking targets in the United Arab Emirates — we’ve finally realized that a civil war is hardly the internal affair of a nation anymore, that the military preparedness of non-state actors has reached destructive sophistication, and that long-running conflicts can easily spread beyond borders, contaminating ideological emotion, causing geopolitical tremors, trade disruption and humanitarian crises on a global scale.

Once again, all politics is international politics. Even the Houthis know it.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.