Extra Cover

Published in Extra Cover

Europe, North Africa, and China: The Geopolitics of Investment for this Decade

In June 2021, G7 leaders met in the UK, where they floated the notion of a deeper partnership on joint strategic investments based on values, transparency, and high standards to address global needs on matters of infrastructural development. They had their eye on the African continent, and the amounts mentioned came to a 100 billion dollars. Six months later, the EU launched its Global Gateway program.

A G7-aligned initiative with a European bent, focusing on investment in connectivity, infrastructure, green transition, and compliance with good governance and human rights-related criteria. Investment amounts cited hovered around 300 billion Euros by 2027.

It’s an ambitious plan. The EU then signals that it wants to push its geopolitical, economic and climate goals especially to its neighbours south of the Mediterranean, although it has not yet defined a clear set of priorities or target regions. One might say that the program does not seem to be in step with impacts on globalization caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, which have forced countries to redesign the supply chains their economies rely on, cutting back on distance and reliance on certain suppliers, looking to rein them in and work in smaller geographic circles where events are more predictable.

The Global Gateway is aligned with the UN’s 2030 Agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals, and carbon goals set out in the Paris Agreement. It is supposed to fund sustainable, high-quality projects that take into account the needs of partner countries and ensure lasting benefits to local communities. This would let a vast network of EU partners develop their societies and economies as well as create investment opportunities for the private sector. That would in turn drive competition, ensure the improvement of labour and environmental standards, improve financial management, help retain local populations and thus reduce involuntary, uncontrollable migration.

When you take a broader view, this project makes sense

. It suits the EU’s ambition of reaching more strategic autonomy along several axes — energy, industry, critical raw materials, security — and will help close gaps, reduce dependency, and downsize carbon footprints through its proposed value chains. To succeed, it will need to bolster a few value chains in regions close to Europe with meaningful green energy potential. Countries along the Mediterranean East and South are ideally poised to answer that demand. Leveraging 300 million Euros to improve schemes and interconnections on sustainable energy, transportation, digitization and other infrastructure, such as railways, harbours and telecommunications, seems to be a primary design. It provides Southern European countries with an opportunity to take advantage of their African relationships, which elevate them in this multilateral dynamic.

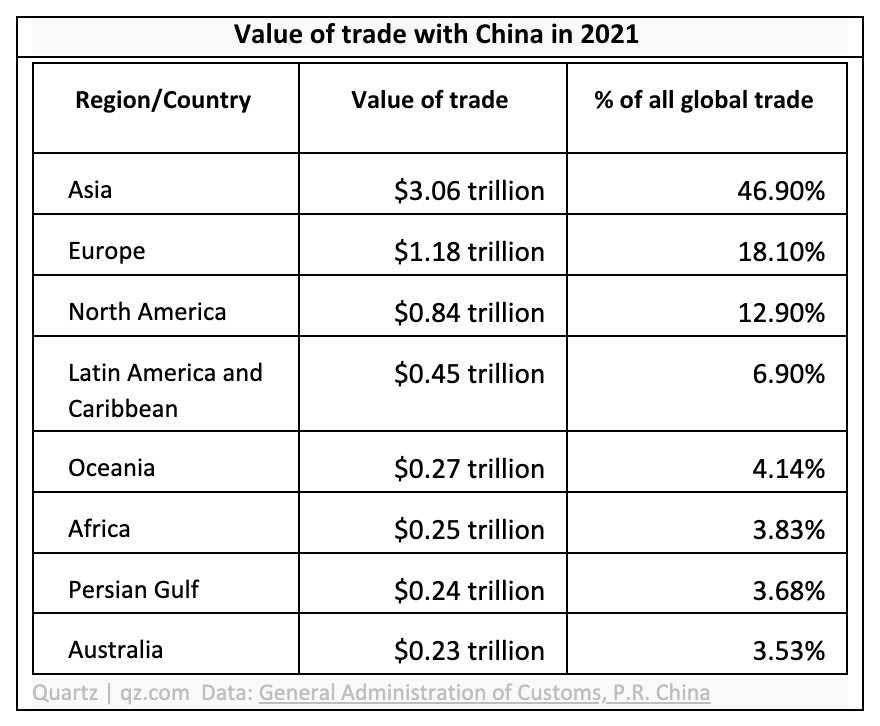

However, the EU has not been able to seize all the available opportunities to help its neighbours develop their economies. Although it has retained dominance on trade and investment in the Middle East and North Africa, the EU faces growing challenges in the region on account of bold moves from China and the Gulf States. It is no secret that the Global Gateway will compete with the Belt and Road Initiative launched by China in 2013. Belt and Road aims to develop infrastructure and trade routes in 147 countries. Such competition makes sense; the European Commission sees itself as a geopolitical player. We now know that China’s colossal efforts have delivered mixed results. Although infrastructure investments did in fact strengthen Chinese influence abroad, especially on the shores of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and Africa, not all of them became economically sustainable. So now’s the time for the EU to assert itself on the criteria that make the EU’s investments stand out.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine laid bare European dependency and forced every European capital to make up for the pull-back from Russian energy imports with new supply — some of it from the south, raising the region’s profile with regard to the development of European economic policy. While Russian activity in the region has been in connection with military efforts, as demonstrated by the presence of the Wagner Group in Libya, Beijing has increased its trade and investment efforts throughout the Middle East and North Africa. These past few years, the USA’s gradual retreat from the Middle East and North Africa has not given way to adequate European capabilities to fill the political void they left behind. In addition to Russia and China, Turkey and the oil states of the Gulf have taken advantage of increased elbow room.

Truly, the European Commission appears to have found a partial footing in that regional approach, with more significant focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, frequently described as a priority region for Global Gateway. In February 2022, the Commission announced eleven strategic lanes (selected out of 55 options) where it wishes to improve connections between Africa and the EU. Unfortunately, North Africa has for the most part been left out of that network. It appears solely as a jumping-off point for the Cairo-Khartoum-Juba-Kampala lane, which would connect Egypt to Central and East Africa. In other words, the key limitation to this approach has been the integration of North Africa as an endpoint for critical raw material supply lines in Africa, instead of a destination that is clearly incorporated in the EU’s industrial value chains.

The EU might, for example, advance true intra-regional interconnection by taking advantage of the flow of investment toward the construction of railways in neighbouring southern countries. Last year, rail transport accounted for 67% of active investment on transportation in Algiers (22.4 million dollars), 59% in Egypt (66.2 million), 40% in Tunisia (4.1 million) and 71% in Morocco (12.7 million dollars). However, investment amounts still fall short of necessity. More importantly, the level of investment concentrates more on national than inter-regional connections. A large multinational construction project is underway which will connect Algiers to Morocco by road, and the EU co-funds it. Yet major gaps persist in North-African connection, especially with Libya. Libya suffers from limited cross-border connections and political volatility, although it is crucial to any future connections between the Maghreb and the Suez.

Algiers has recently decided to apply for membership in the BRICS group. This suggest China has accrued significant political influence in the region. Meanwhile, Egypt has expressed an interest in joining the group as well. Additionally, Algiers signed two agreements with China in 2022 which will focus on Belt and Road development and economic cooperation. This will reinforce strategic ties between the two countries.

If the EU wishes to secure true strategic autonomy, it must match ambition to action. Nearshoring processes are complex and expensive, demanding adequate funds and solid political commitment. Promoting and developing clean energy will support economic and political stability on both shores of the Mediterranean. Neighbouring countries in the South may play a supporting role in the future supply chains of Europe as well as the development of renewable energy. But this can only happen if the EU adapts its approach to ensure due focus to, and investment in the region. The Global Gateway presents an excellent opportunity to do so if the EU acts now. Southern European countries like Portugal have a strong incentive to demonstrate the value of their ties with Africa, their harbour placement, their forward-looking energy plans, and the quality of their diplomacy. The time is now. The context demands that we spring into action.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.